What goes on in the soil during winter?

Winter has arrived, which once again brings to mind how as a young boy I’d be looking out the kitchen window at the now barren landscape wondering what goes on in the soil over the winter? Eventually I’d end up outside with a shovel, but all I ever got was a sore foot from trying to drive the shovel deeper to see what I could find.

After the first snowfall, the soil lies beneath, frozen in a rock-like crust. At first glance it seems lifeless and barren; but millions upon millions of micro-organisms are there, all eager to provide a buffet of nutrients once warm weather returns. Understanding this replenishing process of Mother Nature that occurs deep in the winter garden soil helps us to grasp why our fall gardening practices are so vital.

After the first snowfall, the soil lies beneath, frozen in a rock-like crust. At first glance it seems lifeless and barren; but millions upon millions of micro-organisms are there, all eager to provide a buffet of nutrients once warm weather returns. Understanding this replenishing process of Mother Nature that occurs deep in the winter garden soil helps us to grasp why our fall gardening practices are so vital.

As the earth freezes it forms a top layer, often referred to as the frost layer. Many factors influence how far down it goes. If a lot of snow falls on the ground early in the winter, it can serve as a blanket for the soil underneath. Organic matter plays a role in insulating soil, holding in heat stored below ground during the warmer months. The organic matter can be mulch or compost that gardeners add around the plants, or leaves that fall naturally.

Perennial plants that grow in colder climates, such as many grasses, trees, and shrubs, are able to withstand freezing. They develop root systems below the frost layer. The root systems of these plants perform a number of tasks that protect them from the cold. Roots can release a lot of water from their cells into the surrounding soil. This allows roots to endure colder temperatures without the risk of internal water expanding and damaging root cells. Water within root cells also contains higher concentrations of sugars and salts. They both assist in lowering the freezing point of water inside and between the cells (much like antifreeze!)

Many soil-dwelling animals burrow below the frost layer to survive the winter months. These include insects, frogs, snakes, turtles, worms, and gophers. Some will hibernate. Others simply live on the food that they have collected for their long “vacation” deep underground.

What is even more fascinating? A great number of soil animals have evolved to withstand temperatures below freezing. At least five frog species in North America make their own natural antifreeze. This allows them to become completely frozen for long times without suffering any serious damage to the structures of their cells.

Bacteria and archaea in the winter soil

Soil microbes, like all living organisms, need food and energy. In winter, as the sun’s warmth declines, these are at a premium. Annual plants die after setting seed, while perennials reduce growth and consolidate sugars in their roots; less plant sap is available to feed carbohydrate-loving microbes. With decreased warmth and nutrients, decomposition of organic matter slows as microbes settle toward a quiescent state.

Because of their simple structure, many types of bacteria can freeze without harm. Unlike more complicated organisms, bacteria have membranes that do not burst when their internal fluids turn to ice. With soil rich in humus, bacteria can hibernate through the cold weather well protected within their carbon habitats. Soil that drains well and has humus content around 10% is an ideal environment for overwintering microbes.

Some microbes are even hardier and more primitive than bacteria. These are the archaea, a relatively recent discovery in soil biology. Archaea microorganisms are possibly the most ancient living things and have been found in every known environment from Yellowstone’s hot springs to ice floes in the Arctic. Because they can live and reproduce in extraordinarily harsh ecologies, they are often called extrememophiles “lovers of the extreme”.

Within the soil the mycorrhizal fungi establishes a symbiotic relationship with plant roots by penetrating plant root tissues and surrounding root mass to more effectively take in needed nutrients. The Archaea are microorganisms similar to bacteria that work in the soil to release greater amounts of nutrients so the plant can take in nutrition as required. There is a natural cooperation developed between Archaea and beneficial bacteria making them more effective as a group. Archaea also breaks down organic matter into usable forms that plant roots and mycorrhizal fungi can identify, absorb, and ultimately incorporate for new growth.

Within the soil the mycorrhizal fungi establishes a symbiotic relationship with plant roots by penetrating plant root tissues and surrounding root mass to more effectively take in needed nutrients. The Archaea are microorganisms similar to bacteria that work in the soil to release greater amounts of nutrients so the plant can take in nutrition as required. There is a natural cooperation developed between Archaea and beneficial bacteria making them more effective as a group. Archaea also breaks down organic matter into usable forms that plant roots and mycorrhizal fungi can identify, absorb, and ultimately incorporate for new growth.

While only a few hundred types have been studied, it is probable that thousands of archaea species live in the soil. Until recently, it was thought that only certain bacteria were specialized to convert ammonia into nitrate, a process called nitrification, essential for plant nutrition. Scientists have found that Crenarchaeota archaea are by far the most dominant ammonia oxidizers — up to 3,000 times more abundant than bacteria. Archaea, with their extraordinarily simple cells, are still working at temperatures near 0C when other microbes are fast asleep.

To promote soil life during fall and winter, I lay down compost and make sure to feed the soil with a deep application of compost tea. The compost tea, with its diverse microbial population, supercharges the soil and roots with microbial life. Research shows that the population of microbes around cereal roots can actually grow during winter, generating organic nutrients ready for spring.

Soil Fungi and Mycorrhizae

Many species of soil fungi do not actively survive the winter; instead they set spores. As soon as soil temperature rises, those spores begin to sprout, sending out masses of thread-like hyphae, connecting to their preferred nutrient sources. Most fungi are beneficial to the soil food web, breaking down cellulose to produce plant nutrients and humus. Others can be noxious pests, colonizing mulch, depleting nutrients and attacking plants.

Fungal spores causing rusts, blights, wilting, molds, damping off and root rot are everywhere, floating in the air and settling in the soil. Many gardening experts suggest that the ground be rough dug in fall and weathered during winter to help rid the soil of unwanted fungi and insects. However, this is a two-edged sword. Fall digging disrupts the network of beneficial fungal hyphae, particularly those belonging to mycorrhizae.

Mycorrhizae have been shown to not only strengthen plant development, but also help prevent infestation by noxious fungi. Both spores and hyphae of mycorrhizae withstand winter temperatures and, if left undisturbed, can quickly colonize plant roots in the spring. Another beneficial fungi, trichoderma, actively attack destructive fungi in the soil and on plant surfaces. It even prevents snow molds that form on lawns under snow. Healthy winter soil, full of beneficial fungal microorganisms, defends tender spring seedlings from attack and gives a boost to early growth. You can read more about Soil Biology and Fungi here.

Worms in the winter garden soil

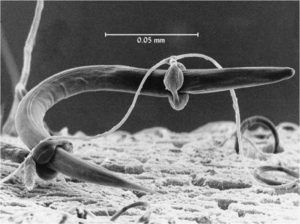

Of all the myriad members of the soil food web, worms have the most interesting winter survival strategies. Before the soil freezes, common earthworms burrow down into the subsoil, below the frost line — as much as six feet deep. There they form a slime-coated ball and hibernate in a state called estivation. Because they are wrapped in mucous, they can survive for long periods without moisture until spring rains wake them from their slumber.

Of all the myriad members of the soil food web, worms have the most interesting winter survival strategies. Before the soil freezes, common earthworms burrow down into the subsoil, below the frost line — as much as six feet deep. There they form a slime-coated ball and hibernate in a state called estivation. Because they are wrapped in mucous, they can survive for long periods without moisture until spring rains wake them from their slumber.

Not all kinds of earthworms make the downward journey. Some lay eggs in cocoons safe in the soil, ready to hatch when conditions are right. Then they settle under leaf litter on top of the soil, where they freeze and die. A type of Northern worm, S. niveus, has evolved an extraordinary method of making it through the winter. S. niveus worms can manufacture glycerol as a kind of antifreeze in their internal fluids. This allows them to supercool their bodies to 15C and survive even the harshest cold.

In a greenhouse, I find that many worms avoid hibernating by finding unfrozen strata of soil, perhaps under a barrel of water that serves as thermal mass, or beneath a plastic bag filled with leaves. Lifting some insulating object, I often find a wriggling mass of worms where I least expect them.

Organic mulching is the recommended and preferred way of protecting all the life in the soil, including worms. Deep mulch reduces fluctuations of soil temperature that cause problems for soil life and over-wintering plants. It also decreases the amount of freezing in the soil and conserves soil moisture.

Plenty of compost and a dose of compost tea and a deep covering of mulch will keep all those wonderful organisms in the soil snug and healthy. With all that life poised to spring into action, you can be sure your next growing season will exceed all your expectations.

Lincoln Landscaping “The Natural Choice”

Mike Kolenut President & CEO

https://lincolnlandscapinginc.com

(201) 848-9699